I go crazy for Tati.

Films like Mon Oncle (1958) and Playtime (1967) are examples of brilliant physical comedy. But then, without knowing half of it there are so many layers. Just when I think these films are like watching works of theatre, they aren’t precisely for their great exploitation of cinematic framing (to give only one example of how every department of Tati’s operates). In Playtime, the spectacular use of wides and long takes with multiple planes allows for an incredible amount of detail, where many narratives unfold simultaneously in vast cityscapes.

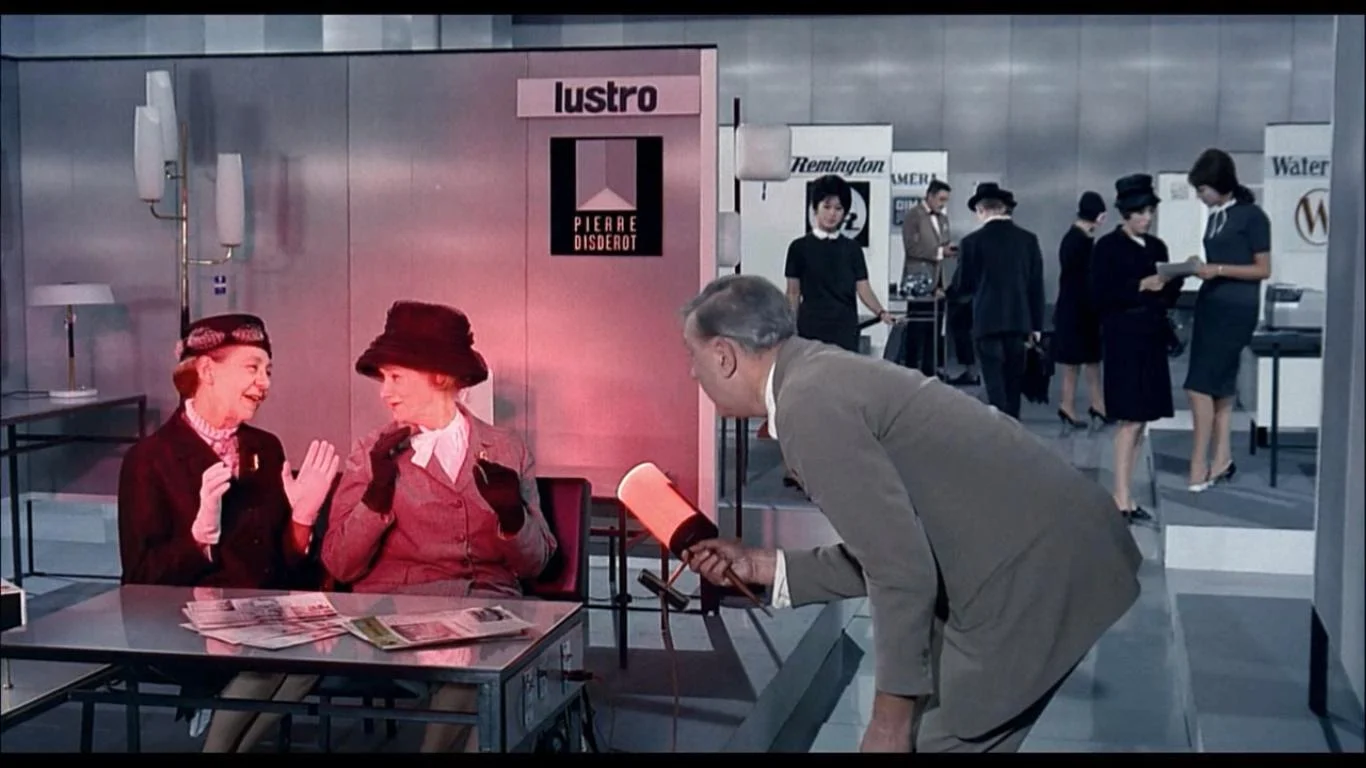

Playtime (1967), Jacques Tati

Considered the greatest comedian of French film, Tati’s encore caricature—the unspeaking Monsieur Hulot—is still however an undeniably theatrical character.

Incomprehensible by way of the pipe that almost never leaves his lips, Hulot is the antithesis of mime at odds with the rhythms and values of contemporary life. He is distinctly apart from the Chaplin’s and Keaton’s because his gags are never a display of prowess, as he bumbles through cities apologetic for the chaos that follows him. His clumsiness, matched only by a curiosity to engage with the inanimate objects of his changing world, are not played for slapstick but are satirical; critical of their functionality and place. In this way, Hulot is a sophisticated character because he embodies a perspective that challenges the changing times in which he finds himself.

Playtime (1967), Jacques Tati

The city is an imagined environment. – Donald, 1995

What these films share is a preoccupation with modern urban experience. Films like Lost In Translation (2003) and Her (2013) explore similar notions, albeit in very different ways. For Tati, themes of connection and authenticity recur, as does a critique of technology as inefficient, dehumanising and cold. Tati’s Hulot is not a comedian in the sense of being both the source and focus of humour as Chaplin and Keaton were, but rather a marker of simpler times who reveals the humour in a changing world by his spontaneous interaction with it. It is distinctly the collision of old and new world values that situates Tati’s unique comedy. Both Mon Oncle (1958) and Playtime (1967) are comical send-ups of modernity for sure, but in appreciating closer it's easy to find that the truths revealed by Tati’s comedies are actually increasingly relevant reflections of ourselves, fifty years on.

Mon Oncle (1958), Jacques Tati

Produced almost ten years apart, Mon Oncle and Playtime specifically address the rapid modernity taken up by France through their occupation with American consumerism after World War II. Tati was one of the only filmmakers to investigate in any depth, the evolving technological-social revolution of French society during the 1950-60s. Through the world of advertising, television series Mad Men (2007) doesn’t do disservice to representations of the rapid growing consumer culture in America during this time—one that was transnationally led by them in France.

But in both Tati films, there is an undeniable pessimism for the human toll that modernity brings about. For Tati, the disappearance of markers of the past underpins the loss of a Paris that is grubby and authentic, distinctive and artisan, patriotic and cultured, warm and personal but most of all: Community. Hulot’s charming, dysfunctional home in an old quarter of Paris where people stop to chat on the street corner is nostalgic. In direct opposition is the sharp silhouetted, cool toned, impersonal and hyper-modern home of his sister, where even the pavements bear designs that draw lines between its inhabitants.

Mon Oncle (1957), Jacques Tati

The private realm of the home is where Mon Oncle largely situates its exploration of newfound innovation. Hulot’s sisters’ house is a confused minimalist facade with an interior that draws comparisons to a hospital ward; truly antiseptic with garish fittings and glowing buttons for absurd automatic functions. She is the image of consumption; porky, her pastel green robe ‘squeaks’ and ‘crunches’ when she moves, rendering her own dialogue comically inaudible. It forces her to move into physical proximity with her husband so that they can hear each other speak. In this context, ‘proximity’ is a decidedly laborious side effect of modern technology in the family home.

Mon Oncle (1958), Jacques Tati. Hulot visits his sister and is faced with an unfamiliar dashboard of lights and buttons in her kitchen.

Playtime however, extends outwards, concentrating almost entirely on the contemporary urban environment by investigating the new physical spaces in which groups and individuals in urbanised postwar industrial Paris live, work and find leisure. In a labyrinth of generic office cubicles Hulot becomes comically lost in the new order of bureaucracy, created to organise that which must simply and continuously be sorted. It’s utterly absurd. The production design is a city-scape of staggering proportion and detail, discovered by a group American tourists who have come to see the ‘real’ Paris. When they find a space-age city of steel, glass, chrome, and plastic, it is only by venturing off their itinerary to embrace the spontaneous, that public spaces adopt a colour and life of their own.

More than anything, I suspect photographers enjoy the film’s overwhelming generosity to the viewer. Each shot offers so much and is held for so long that they eye can wonder about the frame. – Campany, 2013

Shot in generous 70mm, Playtime takes a more meditative approach to visual comedy. Rarely using a close-up but instead employing lingering, long and multi-plane shots, the film has been said to, “liberate and revitalize” the act of looking at the world. This approach to visual design is said to expressly encourage viewers to take in Tati's complex choreography of humans and objects, while distorting the perspectives of both. For example, characters appear to be talking to one another when, cutting to an alternate angle they appear distances apart. The effect is distorting and absurd, further to Tati’s commentary on the dissociation of new urban spaces. It’s this constant visual trickery that sees Hulot not only swaying lost in a sea of identical office cubicles, but out of step in a city which has lost markers of the past. (One can witness this in the remastered trailer for Playtime, below.)

Tati’s mime art consists of discovering humour in ordinary people and events, making us aware of the absurdity of modern life and nostalgic for old-world values. –Lust, 2002

Both films alike represent Hulot as a charming fool whose human incompetence is preference to the inhuman competence of the changing world around him. But what is interesting to reflect on is the mirror Tati’s shiny surfaces place in front of the viewer: not only of the absurdity of modern life and the insignificance of ‘functionality’, but of the optimistic potential for urban dwellers to look to themselves to rediscover spontaneity and connection in the places and people around them.

Rediscovering connection in the people and places we now engage has interesting ramifications in 2015. The spaces of public and private are blurred by an information age where much is shared but nothing online is truly sacred, where solo acts of sharing ironically occur in extreme proximity to others.

It is easy to observe how smart phones have created virtual wormholes that draw people from their tram carriages into a public-private grey area of endless Facebook / Insta / whatever scrolling. Navigating in-between spaces, we strap on wearable technology that allows us to create pleasurable, albeit singular, narratives out of the mundane manner of our everyday lives in passing—which are highly personalised spaces in public. This anesthetising of our experience of surroundings and zoning-out on technology has withdrawn players from the thrill of spontaneous human interaction. It's a basic argument, but a look around your tram will show you what chiropractors are dubbing (and celebrating as a secure business model) as ‘tech neck’ – heads slumped over mobile devices.

Tati’s films, which lament a loss of community, eroded by superfluous designs of modernity, are just as potent now. There is surely no doubt that connections gained through plugging into new technologies draw us away from the human kind. With the sharing of information online slowly eroding cultural barriers, transnational media flows as globalisation (like here) is also partly the debate that Tati begins and which continues still today.

References

Bull, M 2005, ‘No Dead Air! The iPod and the Culture of Mobile Listening’ Leisure Studies, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 343 – 366

Campany, D 2013, ‘Jacques Tati’s Playtime and Photography’, Aperture, no. 212, Fall, pp. 56 – 59

Cardullo, R 2013, ‘The Sound of Silence, the Space of Time: Monsieur Hulot, Comedy, and the Aural-Visual Cinema of Jacques Tati (An Essay and an Interview)’, Contemporary French and Francophone Studies, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 357 - 369

Donald, J 1995, ‘The City, The Cinema: Modern Spaces’, Visual Culture, Routledge, London

Hilliker, L 2002, ‘Modernist Mirror: Jacques Tati and the Parisian Landscape’, The French Review, vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 318 – 329

Lust, A 2002, ‘From the Greek Mimes to Marcel Marceau and Beyond: Mimes, Actors, Pierrots and Clowns: A Chronicle of the Many Visages of Mime in the Theatre’, Scarecrow Press, Maryland USA